This show features two Vermont artists using alternative photographic processes that combine historic and 21st century technologies. Although neither artist appears in their work, each image nonetheless can be viewed as a type of self-portrait.

Thematic similarities running through Rachel and Vaune’s work include the impact of family, the passage of time, and photography’s unrelenting gaze. Both artists give us a complex glimpse into their lives and narratives and provoke us to consider our own.

Vaune Trachtman and Rachel Portesi will be on display September 15 – October 30. There will be an Opening Reception on Friday, September 22, from 4:30 p.m. – 6:30 p.m. and a Meet the Artists events on Sunday, October 8, from 2:30 p.m. – 3:30 p.m.

Vaune Trachtman

The works exhibited here come from two series, Roaming and Now is Always.

“For a long time I have wanted to show them together, and I’m very happy to be able to do so for the first time here at The Putney School, which was so important to me during my junior and senior years in high school,” said Vaune.

Roaming

In her work Roaming, she evokes memories embedded in transitory American landscape, briefly occupying those liminal spaces. The series is informed by her constant, usually unconscious exploration of what it feels like to have lost her parents at an early age.

“They died a long time ago– my father when I was five and my mother when I was 15. I was pretty much on my own after that, and rarely in one place for very long,” Vaune said. “For many years, the view out a car or train window felt more like home than wherever I was living. Over time, I’ve developed a kinship with the other side of that window, that sometimes-mirror. Bridges and highways, trestles and roofs, the husks of industrial towns racing by at two or three in the morning.”

Roaming is primarily about her brief inhabitations of these places, her evanescent homes.

“I want to preserve some of the energy left behind by those who build and pass through these locations, and our lives,” Vaune said. “In these self-portraits as landscapes, I’m seeking a convergence of longing and the land, absence and fullness, stillness and movement, the physical world and the dream state.”

Now is Always

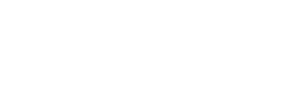

Vaune’s exploration of personal narratives in her Now is Always series collaborates across time with her father’s images from the 1930’s with her own current imagery seamlessly melding archival negatives with contemporary imagery.

Now is Always is supported by a grant from the Vermont Arts Council the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support has come from the Vermont Studio Center and the Tusen Takk Foundation.

“In Now Is Always, I’ve added people to these locations. The people come from archival negatives my father shot in Depression-era Philadelphia, near his father’s drugstore,” Vaune said.

Nearly 90 years after he took the pictures, she was given the negatives, which she combined with her own images, creating a sense of collapsed-yet-expanded time.

“Yes, I want to see what my father saw, and yes, I want him to see what I see—but I also want the viewer to look at the past, and I want the past to look right back. I want viewer and subject to feel each other’s gaze,” she said.

By combining images taken almost a century apart, she also integrates layers of technology and image-making history:

“His 1930’s point-and-shoot, my iPhone, his silver-gelatin negatives, my Photoshop files, and the traditions of ink, elbow grease, and an intaglio press,” Vaune said.

Rachel Portesi

Rachel’s work uses a mix of mediums, polaroids, wet plates, and installation, to examine the commemorative portrait and the use of photography to hold still moments in our changing identities. Thematic similarities in their work include the impact of family, the passage of time, and photography’s unrelenting gaze.

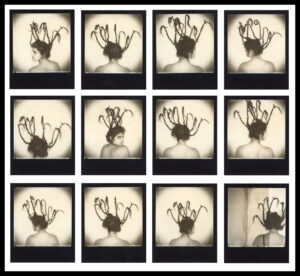

Inspired by the Victorian practice of honoring the dead by making memento mori artwork from hair, Portesi’s Hair Portraits examine her own changing female identity and internal world by making memento mori to honor “past selves”. She too, works to collapse—and expand—a sense of time and narrative by using a mix of media including Polaroids, wet plates, tin types, and video installation

“These images address fertility, sexuality, creativity, nurturing, harmony, and discord. They’re a response — part intuitive, part deliberate — to a time when the scaffolding of my life seemed to disappear,” Rachel said.

“I think some of us assume that the same woman will reemerge on the other side of motherhood. I think I did,” she said. “But suddenly my kids didn’t need me like they had and the Rachel I’d been before becoming a parent was irrelevant, gone. I experienced this as a loss, and grieving it raised questions. Who had I become? Which parts of my old self were best left behind? How did I want to grow?”

She was drawn to early photography and its particularly Victorian interest in loss and death. Commemorative portraits honoring the dead were fashionable and in demand. Another peculiar fixation of the era struck her: hair. Art, sculpture, even mementos of the time consistently used tresses of hair as both object and subject, exploring loss and growth, and presenting a fertile new direction to explore.

These photographs, part of an ongoing series Hair Portraits use wet plate collodion tintype, Polaroids, film, and 3D imagery to explore the nuanced transitions in female identity related to motherhood, aging, and choice as well as the intersection of identity and femininity with the physical world.

“As I engaged with this new mode, my models became conduits of self-reflection — a way to look at the confines of my chosen female role from the outside,” Rachel said. “And there I observed a post-maternal kind of strength wholly different from the role I’d inhabited before motherhood. Looking at them now, these images on the wall, photographs of elaborate hair sculptures constructed in my studio to change. Parts of myself I choose to leave behind. Others I bring with me.”