Story by Darry Madden

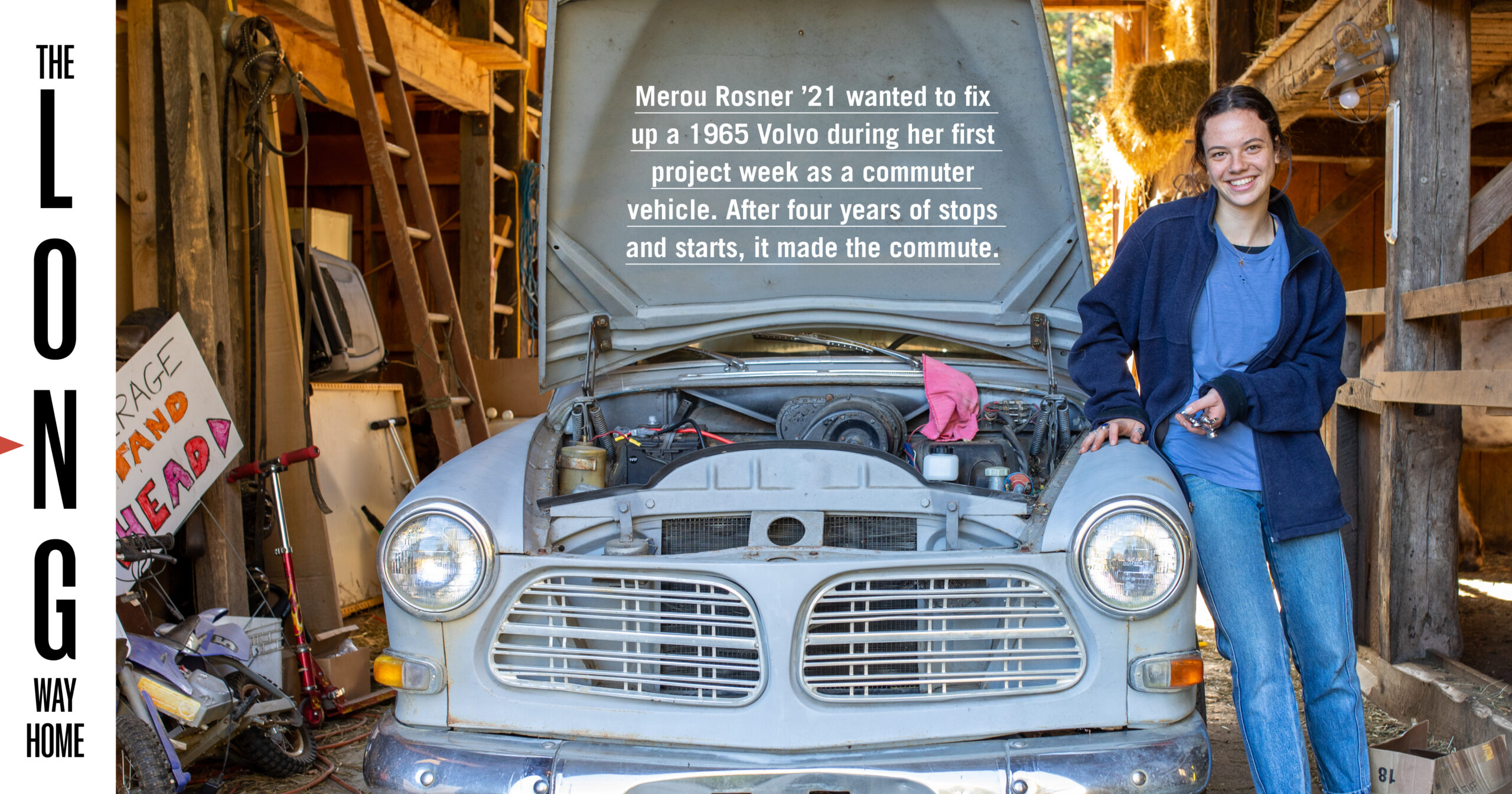

Merou Rosner ’21 wanted to fix up a 1965 Volvo during her first project week as a commuter vehicle. After four years of stops and starts, it made the commute.

The silver and rusted ’65 Volvo in unknown condition arrived one early winter’s night, and was dropped beside the carpentry shop to await its fate.

In the morning, ninth grader Broden Walsh ’21 got behind the wheel while classmate Merou Rosner ’21 and their advisor Glenn Littledale ’76 pushed it into the shed under the gas kiln where Rosner and Walsh would take their first ever whack at fixing up a car. Their goal was to have it running soon enough for the two day students to use it to commute from Marlboro to Putney.

By this point in their first-ever project weeks, Rosner and Walsh had spent one week of the two finding the car, leaving one week to get it running.

They had noticed while unloading the car that the brakes didn’t seem to be working. So they began, naturally, with the emergency brake.

For his part, Littledale told them to research how brakes work and have at it.

“The hardest part was some really rusted parts. Trying to get the brake drum off was a difficult task,” said Rosner. “Glenn would come help and show us a trick, like, jumping on the wrench. But otherwise it was a really easy fix.”

But that was the only fix they accomplished that project week. The Volvo was towed back to Rosner’s house in Marlboro one December afternoon, where it was tucked into the barn as the winter sun went down.

It was too cold to work on it that winter, said Rosner, too dark. And besides, they needed too much from Littledale to do much on their own.

“But then spring came and we decided to continue. We didn’t feel like we’d done enough—we hadn’t fixed the car,” said Rosner. “At that point, we still thought it would not take too, too long. It wouldn’t take our entire high school experience.”

______

Ultimately, it did take her entire high school experience. Rosner watched as her friend and co-mechanic Walsh moved on to other art forms and ideas and experienced a range of project weeks. She watched as nearly every other student at Putney did the same. She would return, over and over, to the car. She worked slowly and deliberately. She worked alone in the garage under Keep, where, if she closed the door, she could capture some of the heat from the faculty apartment. She soldered, welded, wired, bent steel, disassembled and reassembled.

Before heading off to other horizons, Walsh stayed on for a second project week. They wanted to skip all the other likely issues with the car and go straight for the jugular—ignition. They wanted it to start.

“We had an emergency brake. That’s enough, we don’t need full brakes. Let’s just get it started,” remembered Rosner.

To begin, they drained all the fluids and performed an oil change (The oil was “disgusting;” the gas was so full of rust, it was red, and viscous.)

“We knew that it needed a lot of work, but we decided we were going to ignore that for the moment. And so we tried to start the car and nothing happened when we turned the key.”

They tried to hotwire it. They observed that the starter motor and solenoid were not working properly. They still didn’t know if the engine was working, but they knew they couldn’t even test without a functioning starter.

They took it off the car and into the classroom. There, with Littledale’s help, they disassembled the starter, cleaned it out, soldered and braided a new connection.

“We got it back on the car and hotwired it again to see if it would turn over, and it sounded promising. You could hear stuff working,” said Rosner. “And then it caught on fire.”

______

Glenn Littledale served as the advisor on this and many other projects that involved car repair, bike building, or, really, anything mechanical that needed creating or fixing.

“I’m a congenital gear head. I feel like my highest best use is as someone nursing old machinery and that I’m a fake teacher and really more of a machine nurse,” he said.

He has seen many longer term projects through, including individuals with one project, like an orrery (a mechanical model of the solar system), and projects that are passed from student to student, like the telescope that has been the main telescope of the astronomy project for over a decade.

“You can string time together either as the same individual or you can string time together with the project being the unifying idea. The idea of continuity can take a couple of different shapes,” he said.

He thinks of these longer term projects as similar to Putney still teaching traditional chemical darkroom photography—it is explicitly not about instant gratification. The process itself is involved, requiring dedication and investment.

Persistence is, of course, also a key ingredient.

“Merou worked with persistence, she worked with intelligence, she worked with attention to detail. There are very few people who you can hand a wiring diagram to and say, ‘Make sure you have continuity everywhere there appears to be continuity in this system.’ She was not only able to do that, she was able to identify where her car departed from the wiring diagram in front of her. You’re talking about an unusually intelligent person with phenomenal analytical skills. I might offer direct instruction about a thing and then she was routinely able to generalize the result. So she was always looking to leverage what she knew. She retained what she knew. So that made her an especially powerful fledgling mechanic.”

______

When we left our mechanics, they had made a connection between the starter motor and the solenoid. But it didn’t make a strong enough connection, and that was the part that caught aflame.

Solo now (Walsh had gone abroad), Rosner started tracking the ignition system wiring so that she didn’t have to hotwire it for every attempt at a start. And when that was working, she took apart the carburetor, cleaned it, and (miraculously) it was functioning properly. She adjusted the valve timing, which she describes at “super high stakes.”

“Glenn made it a huge deal, which was good because I had to be really careful that no gunk was getting into the engine—I was in the engine at that point.”

There was still no evidence that the engine would function even if all the moments leading up to it turning over were. But all the steps ahead of it were, now, ready to go. And so, with an external fuel system perched on the roof, with Littledale and Pete Guenther ’80 under the hood spraying starter fluid and poised to extinguish any fires, Rosner turned the key.

“And it worked, the car started. The engine runs, the engine works. It sounded pretty amazing, it sounded like a nicely working engine. It wasn’t making some sort of gross sound, it’s just purring. I was so happy. “In my head, I was like, ‘Wow, we’re so close to being done. This is so cool.’”

“So close” is relative. Over the course of the next two years, she stayed with it. She repaired the entire brake system and the fuel system. By the spring of her senior year, she was ready to try and drive it. (It gave her another run for her money by not starting when she tried, but eventually she won out).

With fire extinguisher in hand, she and Littledale backed it out of the garage under Keep. The fifty-six-year-old car drove up the hill past Noyes, past the bare-branched apple trees, up the truck road, turned around at the barn, down to Wender, and back to Keep. Perfectly.

______

On the day of her graduation, Rosner sat behind the wheel of the Volvo and waited with the tractor and hay wagon to process down to the ceremony. Since it had not been ready to commute before graduation, the procession became the goal. She had eight other students crammed in it—maybe more (“I wasn’t sure if that was too heavy for the brakes that I’d done,” she said). When they got to the stand of locust trees and the waiting crowd of family and friends on the East Lawn, they streamed out one after the other—a clown car. Rosner left it there, on the truck road, and ran off hand in hand with a classmate to join the group.

What had she taken away from this experience? Had she, as some teachers had suggested, lost out on the diverse and eclectic opportunities afforded her from a Putney education?

Littledale believes there was an “opportunity cost” to sticking with one project, but that it was worth it. “It’s the same for kids in the theater who are year in year out participating in theater. Or kids who are involved in the arts and just dance all the time. Are you going to tell them not to dance? No, you’re not going to tell them not dance. They are dancers and they love to dance.”

He gave her exhibition about the project the working title “How I Wasted Four Years at Putney” as a nod to that. “That’s true,” he said. “But is it true enough not to do it? Under the umbrella of working on this car there was an awful lot of development.”

“It taught me so much about commitment and about the way that I should be viewing success and feeling satisfaction with the progress that I’ve made. In the beginning, I really thought it was going to be a quick project, I didn’t realize how much it took to fix up a car. And it initially felt disappointing to have the first couple project weeks not really result in something that felt like a huge change. But now after so much time, I’ve learned that none of it was really about having a drivable car. That was always the general goal but there was so much value hidden in every single step,” said Rosner, who is now a first year student at Carnegie-Mellon studying physics.

“And if I had given up, or if I had stopped, or if I had decided it wasn’t giving me enough instant gratification in the beginning, I wouldn’t have learned about that and I wouldn’t have developed a mindset that it doesn’t always have to be solely product-oriented. The project itself can be the reward.”

______

After graduation, the car was parked near the field house, overlooking the alpaca field and the solar panels, an anachronism between a half dozen Subaru Outbacks.

Towards the end of July, Rosner’s father arrived to help get it back to their property in Marlboro. He had helped numerous times before, always with a truck and trailer, but this time—this last time—they decided to drive it home.

The goal had been to inspect it, register it, have it fully legal. Time ran out and it didn’t happen. So they took the back roads to avoid being stopped. He drove the Volvo and she followed behind in the family vehicle. About two miles from their house, two Vermont State Troopers came around the bend in the other lane. Rosner saw them slow down, pause, look at the Volvo with curiosity and suspicion. Her father saw this too.

So he floored it.

“My dad makes it go as fast as he possibly can get it to go, pushing as hard as it will go those last two miles to my house. It was crazy. It felt like we were in a car chase, but we made it.”

Littledale got a kick out of this story.

“I hope Merou remembered to torque the tie rods and torque the axle nuts,” he said.

In the end, it did make the commute, if only once.

`